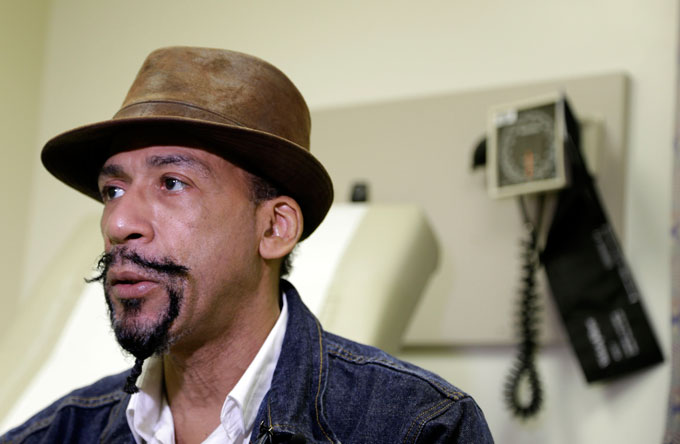

HEALTH SCARE--Michael Lee talks to a reporter about his recent heart surgery and follow-up care at Montefiore Medical Center in New York. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

by Lauran Neergaard

AP Medical Writer

WASHINGTON (AP) — Michael Lee knew he was still in bad shape when he left the hospital five days after emergency heart surgery. But he was so eager to escape the constant prodding and the roommate’s loud TV that he tuned out the nurses’ care instructions.

“I was really tired of Jerry Springer,” the New York man says ruefully. “I was so anxious to get out that it sort of overrode everything else that was going on around me.”

He’s far from alone: Missing out on critical information about what to do at home to get better is one of the main risks for preventable rehospitalizations.

“There couldn’t be a worse time, a less receptive time, to offer people information than the 11 minutes before they leave the building,” said readmissions expert Dr. Eric Coleman of the University of Colorado in Denver.

Hospital readmissions are miserable for patients, and a huge cost — more than $17 billion a year in avoidable Medicare bills alone — for a nation struggling with the price of health care.

Now, with Medicare fining facilities that don’t reduce readmissions enough, the nation is at a crossroads as hospitals begin to take action.

“Patients leave the hospital not necessarily when they’re well but when they’re on the road to recovery,” said Dr. David Goodman, who led a new study from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care that shows different parts of the country do a better job at keeping those people at home.

The Dartmouth study was commissioned by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which then invited the AP as a partner to explore through focus groups it organized what happens at the hospital level that makes readmissions so difficult to solve.

In Portland, Ore., nurses at Oregon Health & Science University start teaching heart failure patients what they’ll need to do at home on their first day in the hospital, instead of just on their last day.

In Salt Lake City, a nurse acts as a navigator, connecting high-risk University of Utah patients with community doctors for follow-up treatment and ensuring both sides know exactly what’s supposed to happen when they leave the hospital.

Some techniques are emerging as key, Coleman said: Having patients prove they understand by teaching back to the nurse. Role-playing how they’d handle problems. Finding a patient goal to target, like the grandmother who wants her heart failure controlled enough that her feet don’t swell out of her Sunday shoes.