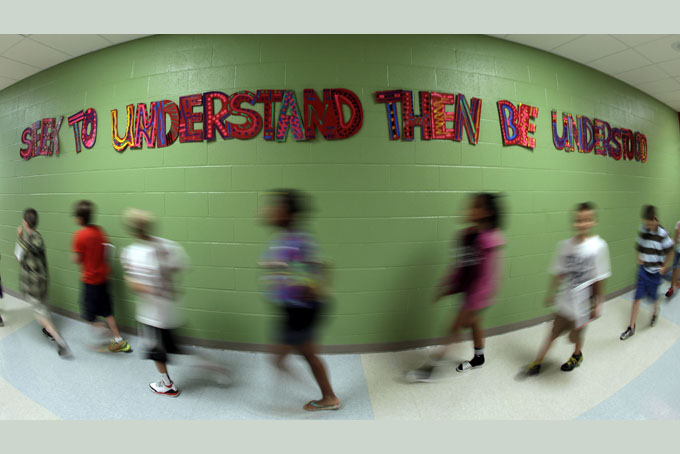

Students walk between classes past a sign extolling a leadership principle at Indian Trails Elementary school in Independence, Mo. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

by Heather Hollingsworth

Associated Press Writer

INDEPENDENCE, Mo. (AP) — One year after Johnathan Kent kicked his principal and school “went all bad,” the 8-year-old was recognized at a recent assembly as the “Star of the Month” for being polite and helping out his teachers.

The third-grader’s explanation for the turnaround: “I’m not doing what I did last year.”

But Emily Cross, the principal of Indian Trails Elementary on the outskirts of Kansas City, Mo., is giving some credit to a program the school began using last year that is built around the late self-help guru Stephen Covey’s best-selling “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.” A 25th anniversary edition of the 1989 book will be released in November.

Second-grader Jacob Nix works on setting goals with his teacher at Indian Trails Elementary school in Independence, Mo. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

The nearly 1,500 mostly elementary schools using the program — called “The Leader in Me” — teach principles from the book, including “think win-win,” ”seek first to understand, then to be understood” and “synergize.” Teachers, for example, might ask students how historical figures like George Washington might have used them.

And if a student gets into trouble, teachers and principals ask what habit could have helped him or her avoid the scrape.

When Johnathan’s principal asked the boy what habit led to his turnaround, he quickly responded, “Do first things first.” He said he didn’t finish his work last year.

Students typically are assigned leadership roles that range from class greeter to fish-tank cleaner. They also keep a leadership notebook in which they chart growth in an academic area. The notebooks also track a personal goal, such as the time spent learning to tie their shoes. Cross said the tracking is a big motivator for Johnathan.

“He sees that when I’m in class putting first things first, my dot on my graph is going up, and he’s proud,” Cross said. “He’s very confident now, and he wasn’t last year.”

The Leader in Me, which has started branching out into preschools and middle schools, is one of “literally dozens” of programs seeking to improve the school climate, said Paul Baumann, director of the National Center for Learning and Civic Engagement at the Denver-based Education Commission of the States, a nonpartisan group that researches education policy. He said most of the programs are run by nonprofits. The cost of the Leader in Me was “pretty high” in comparison, he said.

For a 400-student school, adopting the Leader in Me program would cost between $45,000 and $60,000 over the first three years.

The program’s developer, FranklinCovey, acknowledges that the expense is one of the biggest challenges. Some schools are able to cover the cost using federal Title I money that’s awarded to schools that serve large numbers of low-income students. And for schools that need help, foundations, community Chambers of Commerce or businesses might be asked to help cover the cost, said Meg Thompson, who oversees the program for Salt Lake City-based FranklinCovey.

Not everyone is sold though. Lakeview Elementary in Kirkland, Wash., a Seattle suburb, dropped the program this year after parents complained. Lake Elementary parent Paul Devries said he found the program “cult-like” and “objected to the group mentality.” Some schools offer training sessions for parents.

“It’s our responsibility as parents to teach values to our kids, not for kids to come home and teach FranklinCovey’s values to us,” said Devries, 53, a fishery scientist and water resource engineer. “Kids should be able to be creative and think for themselves and not be automatons and repeat the seven habits.”

Asked how many schools had dropped out, FranklinCovey said that would be hard to calculate.

Before his death in July 2012, Covey disputed criticism that he simply repackaged his Mormon faith in the “Seven Habits.”

Backers say the program exceeded expectations.

“It is easier for kids at 5, 6, 7 to learn the habits than it is for us adults,” said Joel Katte, principal of Meadowthorpe Elementary in Lexington, Ky., where student leadership assemblies feature students singing about and performing skits about the habits. “It’s kind of a first language for them.”

The program got its start in 1999 when Muriel Summers, principal of A.B. Combs Elementary in Lexington, asked Covey whether he thought the habits could be taught to children. FranklinCovey provided free training for her staff.

“We started to see amazing results,” Summers said. “We saw children really being recognized for what they do well, not what they didn’t do well. And we started to love them through their challenges.”

Covey documented the experience at Summers’ school and others in a 2008 book, and the program expanded. Besides the U.S., it’s also being used in more than 35 counties, including Australia, Japan and China. Sean Covey, executive vice president at FranklinCovey and one of Covey’s sons, said the company’s goal is to have the Leader in Me program used in 10 percent of U.S. schools.

The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University examined two elementary schools using the program and found that students reported their teachers were nicer, while staff reported improved student behavior. That was the experience at Benjamin Harrison Elementary in Marion, Ohio, where discipline problems declined as troublemakers turned into “role model” students, principal Leah Filliater said.

“I think they saw themselves differently, and I think staff treated them a little differently,” Filliater said. “I think it’s a different philosophy that each student can be great at something.”