Former University of Pittsburgh and NFL Hall of Fame running back Tony Dorsett stands on the sideline before the start of an NCAA football game between Pittsburgh and Notre Dame on Saturday, Nov. 9, 2013, in Pittsburgh. (AP Photo/Keith Srakocic)

by Steve Almasy and Eliott C. McLaughlin

(CNN) — Tony Dorsett recalls a 1984 game against the Philadelphia Eagles when he was streaking up the field and an opposing player slammed into him. One helmet plowed into another.

Dorsett’s head snapped back, his helmet was knocked askew.

“He blew me up,” Dorsett told CNN’s Wolf Blitzer. “I don’t remember the second half of that game, but I do remember that hit.”

Dorsett compared the hit to a freight train hitting a Volkswagen.

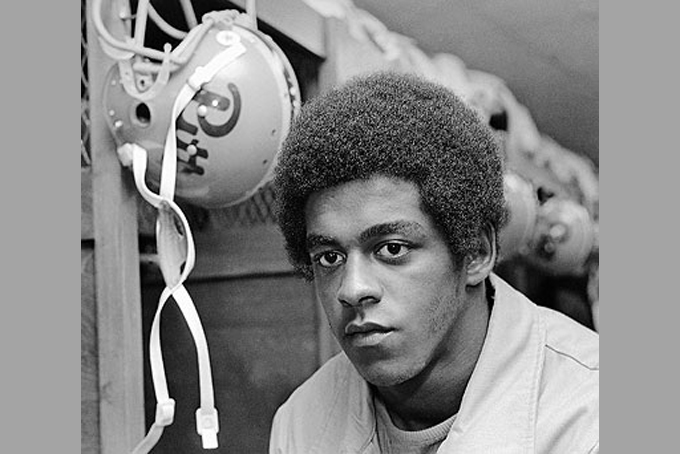

1976 Heisman winner Tony Dorsett (AP Photo/Harry Cabluck)

These days Dorsett is worried about the cumulative effects of hits like the one Ray Ellis laid on him that day.

In the past two years, Dorsett’s memory has given him increasing trouble.

On Monday, doctors at UCLA told Dorsett, 59, he has chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the Hall of Famer said.

CTE is a progressive degenerative brain disease found in some athletes with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

The only way to definitely diagnose CTE is after death, by analyzing brain tissue and finding microscopic clumps of an abnormal protein called tau, which has been found in the brains of dozens of former NFL players.

However, a pilot study at UCLA may have found tau in the brains of living retired players. Some scientists say finding the disease in the brains of living players is the “holy grail” of CTE research, providing a means to diagnose and treat it, and the UCLA study may be an important first step.

Using a scan called a positron emission tomography, or PET, typically used to measure nascent Alzheimer’s disease, researchers inject the players with a radioactive marker that travels through the body, crosses the blood-brain barrier and latches on to tau. Then, the players’ brains are scanned.

“We found (the tau) in their brains. It lit up,” Dr. Gary Small, professor of psychiatry at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA and lead author of the study, said in February.

Dr. Joseph Maroon, a neurosurgeon who works with the Pittsburgh Steelers, cautioned Thursday that the CTE diagnoses of Dorsett (and two other living former players) need further study.

“This is very, very preliminary,” he told Sportsradio 93-7 The Fan in Pittsburgh. “There are many, many causes of dementia or progressive memory loss, particularly when you get over 60 or 70 years of age. … It’s something to obviously be concerned about, and the question is what can be done about it?”

Dorsett said the diagnosis explains a lot about his forgetting where he is driving and his mood swings.

“Memory loss, more so than anything it’s been my big deal,” he said. “Sometimes you can have sensitivity to light and things like that. But my thing was not remembering. I’ve been taking my daughters to practice for years and all of a sudden I forget how to get there.”

His daughters are afraid, he said. They wonder which father they will get. Will he be the happy dad or the one in a bad mood.

For others known to have had CTE, symptoms include depression, aggression and disorientation.

In 2002, Mike Webster, a Hall of Fame center for the Pittsburgh Steelers, was the first former NFL player to be diagnosed with CTE. After his retirement, Webster suffered from amnesia, dementia, depression and bone and muscle pain.

Unlike Webster, who spent his career smashing into opposition linemen many times a game and in practice, Dorsett was a superfast running back who made his enemies miss by darting past them or with a quick spin to avoid contact.

He won the Heisman Trophy as college football’s best player in 1976 and became an instant NFL star on the league’s most popular team, the Dallas Cowboys.

He played 11 seasons and gained 12,739 yards, eighth best of all time. His 99-yard run in 1982 is an NFL record. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1994.

Now he looks in a mirror and wonders.

“And I say who are you? What are you becoming?” he said. “It’s very frustrating to be a person that’s been so outgoing, then all of a sudden, I’m like a couch potato.”

Other athletes have demonstrated erratic behavior, such as Pittsburgh Steelers offensive lineman Justin Strzelczyk, 36, who died in a 2004 high-speed chase. Cincinnati Bengals wide receiver Chris Henry died at age 26 after falling from the bed of a moving pickup during a fight with his fiancée.

Some who showed signs of the disease have taken their own lives, including former Philadelphia Eagles defensive back Andre Waters, who shot himself in 2006; Terry Long, a former Pittsburgh Steelers offensive lineman who killed himself by drinking antifreeze; and Junior Seau, the former linebacker who killed himself last year at the age of 43.

Dorsett said that won’t happen to him.

“I’m going to beat this. Trust me,” he said.

Dorsett pins much of the blame for his health issues on team owners. He said a $765 million settlement of a concussion lawsuit with the NFL was not enough.

“I can’t put a price on my health. The owners knew (about the dangers of concussions) for years and they looked the other way, and they kept putting us players in harm’s way.”

The deal calls for the NFL to pay for medical exams, concussion-related compensation, medical research for retired NFL players and their families, and litigation expenses, according to a court document filed in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia.

The agreement still needs to be approved by the judge assigned to the case, which involved more than 4,500 plaintiffs.