“Quit Playin”

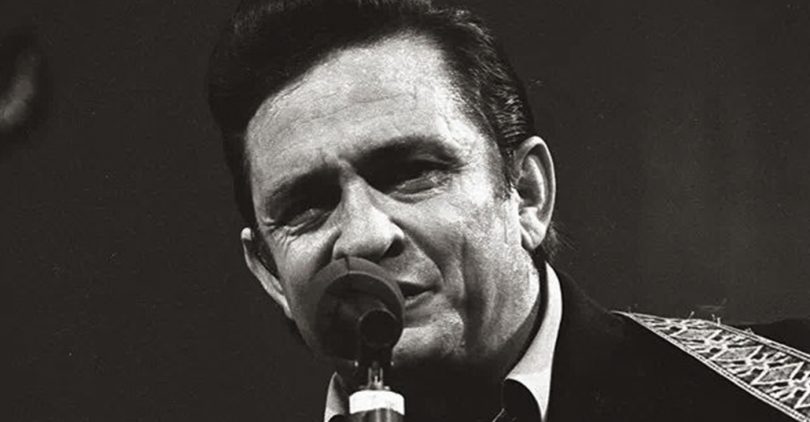

You can run on for a long time…but sooner or later God will cut you down.– Johnny Cash

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In most instances when you think of the civil rights movement and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., you think of names like Jesse Jackson and Joan Baez, Maya Angelou and Coretta Scott King. Lots of names are readily paired or associated with America’s greatest prophet. As I listened to the words of a song recently, I was captured by the similarity in Dr. King’s words and the words of the ultimate country and western entertainer and one of the few with crossover appeal: the late J. R. (Johnny) Cash.

King was born 10 months before the Great Depression and Cash came in two years into the world’s most pervasive economic disaster. King made his debut in Atlanta, Georgia and Kingsland, Arkansas was never heard of before Johnny Cash gained national notoriety and declared that town of 500 or so as his homeplace.

Upon hearing that a “New Deal Colony” had been established in Dyess, Arkansas, Cash, his parents and seven siblings moved.

The deal was that if you worked the land you could eventually own it. Before too long, Cash was working the cotton fields and learned to sing as he worked. Now, parenthetically, if you didn’t understand what the blues was about, here’s the lesson: hard work and poverty produce all types of creativity.

Michael King’s story was quite different. He was the middle son to a well-educated and powerful minister who later changed his name to Martin. The elder King did his best to physically whip King into “somebodyness,” but ultimately, it was his father’s refusal to answer to being called “boy” that molded him.

Michael King’s story was quite different. He was the middle son to a well-educated and powerful minister who later changed his name to Martin. The elder King did his best to physically whip King into “somebodyness,” but ultimately, it was his father’s refusal to answer to being called “boy” that molded him.

When you grow up watching your daddy leading protests, it sets a moral and social delimiter that is not easily forsaken.

By 1955, Johnny Cash has made his first recording, a song called, “Hey Porter.” That same year, historians began recording King’s every word after he began the Montgomery Bus boycott. Cash’s song asked a train porter, “How long before we cross the Mason Dixon Line?” Meanwhile, King was trying to eradicate the residue of slavery and Jim Crow that came with that line.

1957 saw Cash’s “I Walk the Line” on the radio airwaves and Dr. King was walking the line too, but it was a protest line. King incorporated the SCLC that same year.

In 1965, Johnny Cash suffered his first arrest. Cash had become addicted to narcotics. His autobiography spoke of the guilt he felt when his brother was literally cut in half by a table saw. King was in Selma in 1965 bemoaning a Bloody Sunday experience of another type. 1967 brought Cash his first Grammy Award. In 1967, King was fighting LBJ over the poor and the Vietnam War and the awards just stopped. The Nobel Peace prize winner had become persona non grata.

On March 1, 1968, Johnny Cash married his stage partner and musical sidekick, June Carter. Thirty-three days later, Dr. King was divorced from this life by the power vested in an assassin’s bullet. Cash went on to record a song written by Kris Kristofferson, “They Killed Him.” The song was dedicated to the lives of Gandhi, King, the Kennedy’s and Jesus Christ.

Their lives were as stark and different as night and day. But in death, Cash and King left words that are conjoined in the universal truth of our existence.

Cash and King understood that time would eventually bring about a just end. The two men agreed one thing: you can run a long time, but the arc of the universe is going to bend toward the just and cut down the unjust.

Cash and King implied that immoral men, like Donald John Trump, must fear their day of reckoning. The end result will not be good for them.

#JusticeWillCome #KarmaIsReal

Vincent L. Hall is an activist, author and award-winning writer for the Texas Metro News.