AP Photo/Lynne Sladky

by Jody L. Herman, University of California, Los Angeles; Andrew Ryan Flores, American University, and Kathryn K. O’Neill, University of California, Los Angeles

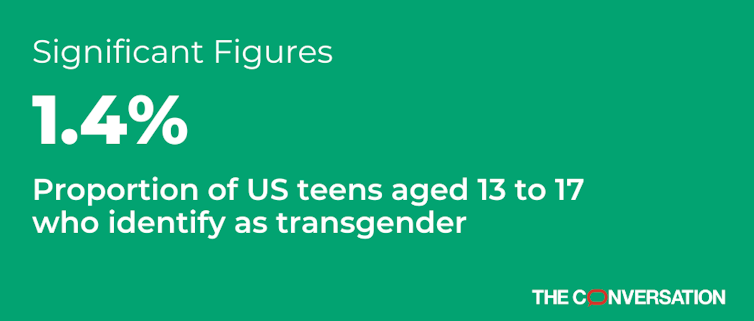

In our recent analysis of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a representative health survey of high school-age Americans at the school district, state and national levels, we found that about 1.4% of youths ages 13 to 17 identify as transgender in the U.S. That proportion amounts to approximately 300,000 transgender young people.

The results update those from our 2017 study, which, at the time, suggested that 0.7% of teens ages 13 to 17 openly identified as transgender.

While some people might assume that this means the number of trans teens has doubled in just five years, our results shouldn’t be read that way. There are a few possible reasons for the larger estimate this time around.

Not necessarily a trend

When compiling the 2017 report, we didn’t have relevant survey data from American teens. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey did not include a transgender status question until 2017, and the results of that survey were still being compiled when we published our report. So we relied on patterns among young adults who openly identified as transgender to arrive at a credible estimate of 0.7% for the younger cohort.

In its 2017 and 2019 studies, however, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey did include a question about transgender status on the questionnaires administered in 15 states.

We used the survey responses from youths in these 15 states to create a statistical model that takes into account both individual- and state-level characteristics, and combined the results with census data to arrive at credible estimates for all states and the District of Columbia, along with a national estimate.

This process is called multilevel regression and poststratification, and it’s an increasingly popular modeling strategy in the social, political and health sciences.

This method is an improvement upon the methods we relied upon in our 2017 report. Therefore, it’s possible that the higher proportion in 2022 is less an indication of change over time and more a reflection of better measures.

Open minds

Nevertheless, both studies found that young people are more likely than older people to identify as transgender. We found only 0.5% of adults 18 and older identified as transgender, which amounts to about 1.3 million adults.

Why the discrepancy?

There is no single reason that explains it, but studies have shown that younger people tend to have warmer attitudes toward transgender people than older individuals. At the same time, adults in the U.S. are becoming more open to transgender rights.

Together, these two trends suggest that transgender young people are in an environment where it is safer and less stigmatizing to openly identify.

Furthermore, the language around trans identities has evolved over time, creating new identity categories – such as nonbinary, gender nonconforming or genderqueer – that fit under the umbrella term “transgender.” This may influence how people respond to surveys. For example, the 2015 United States Transgender Survey found that among those who identified as nonbinary, 61% were 18 to 24 years old, while only 5% were older than 44.

A snapshot of affected teens

Numerous state legislatures have proposed – while others have passed – policies restricting the ability of transgender young people to participate in sports or receive gender-affirming health care. Stigmatizing policies can adversely affect transgender people and have even been linked to suicide attempts.

It’s worth noting that our estimates are only of those transgender young people who said “yes” to the question of whether they were trans in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. It’s possible that some of the respondents would not want to disclose these aspects of themselves in a survey setting. There may also be some people who have a current gender identity or expression that is different from their assigned sex at birth who do not currently identify as transgender.

Our estimates, then, provide a snapshot of what could be be an even larger population that may be affected by legislation.

Jody L. Herman, Senior Scholar of Public Policy at the Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles; Andrew Ryan Flores, Visiting Scholar at the Williams Institute and Assistant Professor of Government, American University, and Kathryn K. O’Neill, Policy Analyst at the Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.